In the late 19th century, a new group of American journalists called “muckrakers” sprang up in reaction to the political and corporate graft that lay just below the glittering, economically prosperous surface of the Gilded age. The muckrakers emerged alongside the yellow journalism of the 1890s that had accustomed the public to sensationalist articles. However, the muckrakers moved away from vapid sensationalism and turned toward social-justice oriented, investigative journalism.

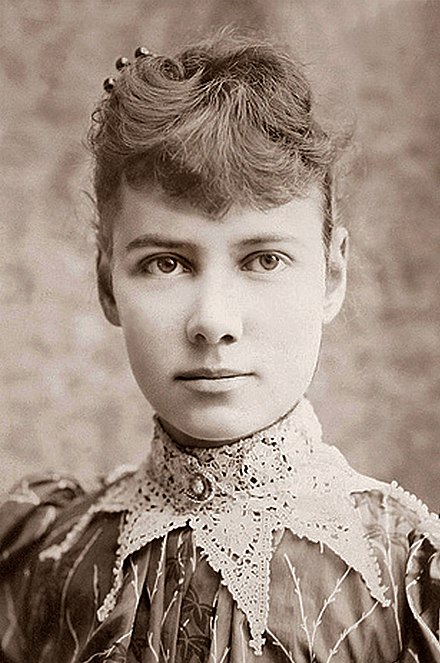

This journalistic trend guided the nation into the progressive age, uncovering many a political scandal or corporate crime. One of these muckrakers, widely considered to be a pioneer of the movement, set herself apart from the rest through a daring investigative exercise and a revolutionary criticism of existing institutions, an endeavor that fomented real world change for one of society’s most ostracized groups. Her name was Nellie Bly.

Born 1864 as Elizabeth Jane Cochran into a wealthy Pennsylvania family, Bly’s early life was characterized by turmoil and financial hardship following the death of her father and the loss of his profitable mill. Accustomed to the turmoil and struggle of being somewhat impoverished in the late 1800s, Bly’s feisty personality catapulted her into a flourishing journalistic career at a time when female journalists were few and far between.

As a young woman, Bly came across a piece in the Pittsburgh Dispatch titled “What Girls are Good For.” Enraged by the blatant misogyny, she responded to the news agency in a spirited and eloquent letter to the editor. The Dispatch responded, inviting her to join them as a full-time journalist, a proposal that she readily accepted. Her public persona thus became “Nellie Bly,” as it was seen unfit for women to write under their birth names, and she was soon to become one of America’s most idolized and influential journalists, a pioneer of investigative journalism.

Bly’s time with the Pittsburgh Dispatch was short, for at a mere 23 years old, she marched confidently into the office of Joseph Pulitzer, one of the two most prolific sensationalist journalists of the time, and secured her position writing for the New York World. It was here that she would pen articles on political graft and the sad realities of poverty, where she would embark on her famed journey around the world in a mere 72 days, where she would interview controversial leftist intellectuals such as Emma Goldman. And it was here that investigative journalism would flourish.

She had hoped to write articles regarding the struggles of impoverished immigrants in an exploitative and rather nativist America, yet Pulitzer, concerned not with the truth but only with what would fatten his pocketbook, proposed that the young woman write an article on the infamous Blackwell Island mental asylum. Bly not only accepted this bold proposal, but challenged herself to write from the point of view of an insider, rather than as an alienated journalist asking impersonal questions to uninterested participants. Bly would feign insanity, something rather easy to do as a young, independent woman in 1887, and be admitted to Blackwell Island for ten days with only a vague assurance that her stunt would end with her restored freedom.

Her adventure began on the streets of New York. Masquerading as an impoverished immigrant, Bly had no trouble being labeled insane and was thereby sent to Blackwell Island. The articles she wrote upon her release took the form of a narrative, in which she went to great lengths to ensure that each and every detail was true to her experience as a mad woman. The firsthand account and the care she took to record the tales of other women on Blackwell, some who were kind, and scared, and rather sane, and others who were mad and severely mistreated, were particularly effective at portraying the inhospitable conditions on the Island.

Bly’s riveting, heart-wrenching accounts of her time in the asylum make it clear that the women were treated more like prisoners than patients, and perhaps even more like livestock than prisoners. There were, at the time, 1,600 women boxed in by the ocean upon the loathsome island. Many were evidently as sane as Bly herself, yet were treated as if they were as mad as could be. And those who truly were plagued by insanity were managed as inhuman beasts by the so-called “nurses.”

This treatment, recounted Bly, inflicted insanity upon the sane and was beyond ineffective at treating any sort of madness. One patient who accompanied Bly on her journey (essentially an inmate at Blackwell) was Tillie Maynard; her descent into madness was due to the dreadful conditions in the asylum, which is made clear in Bly’s articles.

“What, excepting torture, would produce insanity quicker than this treatment?” laments Bly, “Here is a class of women sent to be cured?”

Every detail depicted – the authoritarian demeanor of the nurses, the odious state of the food, the night time conditions, the physical abuse of the poor women – paints the asylum as a place of absolute depravity and sadism. Bly aptly compares the asylum (a sad irony considering the nature of the word “asylum”) to a “human rat-trap.” Her vivid description of the asylum leads one to believe that a rat trap would be better than the accursed island. “Compare this with a criminal,” writes Bly, “who is given every chance to prove his innocence.”

Perhaps the most saddening line of the famed articles occurs before Bly even entered the unsanctified halls of Blackwell Island Asylum: “And he left the poor girl condemned to an insane asylum, probably for life, without giving her one feeble chance to prove her sanity.”

Pulitzer knew the story would sell, and Bly knew it would reveal institutionalized abuses. This was the first glimpse most readers were granted into an insane asylum. It shocked many to their very core. Something had to be done.

And for the first time since perhaps Dorothea Dix advocated for the rights of the mentally ill, someone had humanized a group of individuals who were so systematically dehumanized that their abuse had become the norm. Through investigative journalism, Bly elicited sympathy from the public, bringing tangible change to mental hospitals. Patients were finally able to retain at least some level of dignity and humanity. Although the process of asylum reform remained incomplete for quite some time, and arguably remains incomplete today, it was ultimately Bly’s harrowing journalistic narrative that began the long and tumultuous process in rehumanizing the ostracized mentally ill.