How Are We Graded, And Is It Fair?

February 9, 2018

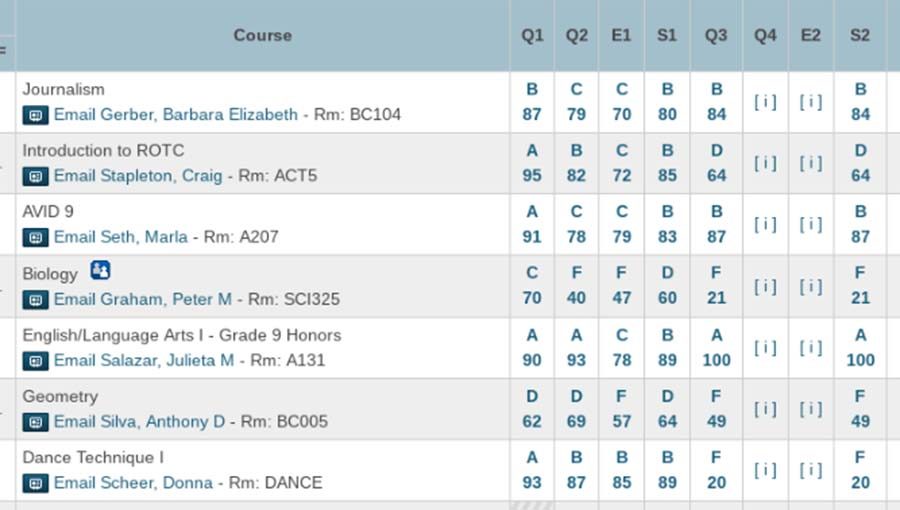

With the new semester just beginning, students have a fresh slate, another chance to get their grades up. But for some, the pressure of difficult classes continues, which leads some to question, How do different teachers weigh the grades in their classes? Are the grades weighted fairly? And how do students feel about these policies?

This is not a new issue. Everyone has heard the story of “overbearing” parents marching down to the principal’s office complaining that their child’s work was unfairly graded. The general response is an eye roll, but could they be right?

Here at Santa Fe High, teachers use many different types of grading scales.

Mr. Eadie, the school’s AP coordinator, recently changed the way he weighs grades in his AP Psychology class. Exams now weigh 50 percent (up from 40), projects weigh 35 percent (up from 30), and formative assessments and class participation weigh 15 percent (down from 30). Mr. Eadie now collects homework only on the day of exams, giving students a prolonged time to finish assignments. He told his second-period class that he made the changes to make the course more like a college-level class.

Miranda Archuleta, a junior in the class, states, “I understand that he is upset that people are performing less than he thinks they should, but it’s not really fair [to the students] to change the policy so drastically, so late in the year, because [the exam] is 50 percent of your grade. If you don’t get a good grade on that, you won’t get a good grade in the class.”

Physics teacher Ms. Nugent says that for her classes, major grades, such as tests and labs, weigh 70 percent, minor assignments weigh 30 percent, and class participation does not count for a grade. She uses a broken-line curve on major tests, which is “looking for natural breaks in grades, when nobody makes a grade in a certain range” and then adjusting grades as one would with a normal curve. She uses this same curve for the entire quarter grade.

English teacher Mr. Dean says that his tests, homework, and other assignments all have an equal weight in his grade book. In Mr. Dean’s class, everything is on a four-point scale, which then translates to a percentage. A score of four turns into a 100 percent, a three is a 90 percent, a two is a 75 percent, and so on. Part of his grading policy is also to get rid of old grades periodically as students advance in his class. “The older scores go away as people get better. So if they start out as a two, but they can then show that they are a three, the older score would go away.”

Senior Kai Galley said, “I appreciate Dean’s grading system. I believe it encourages students to continue to improve. It’s fair and truly reflects the grade students deserve.”

Students may prefer certain grading systems, but is there one perfect policy that can improve schools and student well-being? According to one experiment, yes.

Douglas Reeves, in his book Leading Change in Your School, talks about Ben Davis High School in Indiana where teachers focused on direct feedback and intervention with students. Their plan of action included the following: early, frequent, and decisive intervention; parent connections; tutoring, both personal and electronic; managing students’ choices with decisive curriculum interventions; in-school assistance; and reformed grading systems.

For example, the teachers at Ben Davis listed students who were at risk of failing every three weeks in the school year so that counselors, parents, teachers and administrators could assist and support them. They also changed their grading policies to get rid of “the use of a zero grade, the inappropriate use of averages, and the assignment of poor grades as punishment.”

The results were positive. With these policies in place, they had 1,006 fewer course failures, a 32 percent increase in the enrollment of AP classes, a 67 percent reduction in suspensions, a swell in art electives, and a drop in tardiness and class cuts.

Reeves stresses the importance of a no-zero policy. He suggests that using a zero as a repercussion for not doing work is “so ineffective it’s toxic.” He states that teachers should instead just have students do the work with no exceptions: “Before, during, or after school, during study periods, at ‘quiet tables’ at lunch, or in other settings.”

Many other associations and individuals agree with Reeves. In an article by the National School Board Association, T.R. Guskey, a professor of education at the University of Kentucky, states that zeros “can cause students to withdraw from learning.”

Mr. Dean supports this policy, saying he doesn’t give zeros because he does not want to send kids to E2020, where he believes students do not learn as much as they would in a classroom setting.

Ms. Nugent, however, does not ascribe to the no-zero policy: “For the past 30 years, we have been enabling students by giving them grades they have not earned, and it has weakened education, in my opinion.” She also states that when she attended a National School Board meeting last October, she learned that colleges were “so disturbed by [grade] inflation that some of them barely even consider GPA [when accepting students into their schools].” Ms. Nugent stated, “If ‘A’ doesn’t mean excellent, then grades are meaningless.”

It’s tough to find research supporting the use of zeros, but there are still some advocates. Theresa Mitchell Dudley, president of the Prince George’s County Educators’ Association, in Maryland, told NEA Today that a no-zero policy is “problematic.” She criticizes the policy for not preparing students for the real world and teaching them that timeliness means nothing.

Clearly there are polarized opinions about grading policies, but an obvious fact is that students are individuals, and one system might work better for one than another.

So, are Santa Fe High’s many grading systems fair? Is one type better than another? Leave a comment below, and join the conversation.