YouTube star and YA author John Green has in recent years taken up the fight against the widespread malady of tuberculosis, an infectious disease. TB is an extremely prolific killer, second only to Covid-19. Approximately 1.3 million individuals died from the disease in 2022 alone, according to data from the World Health Organization.

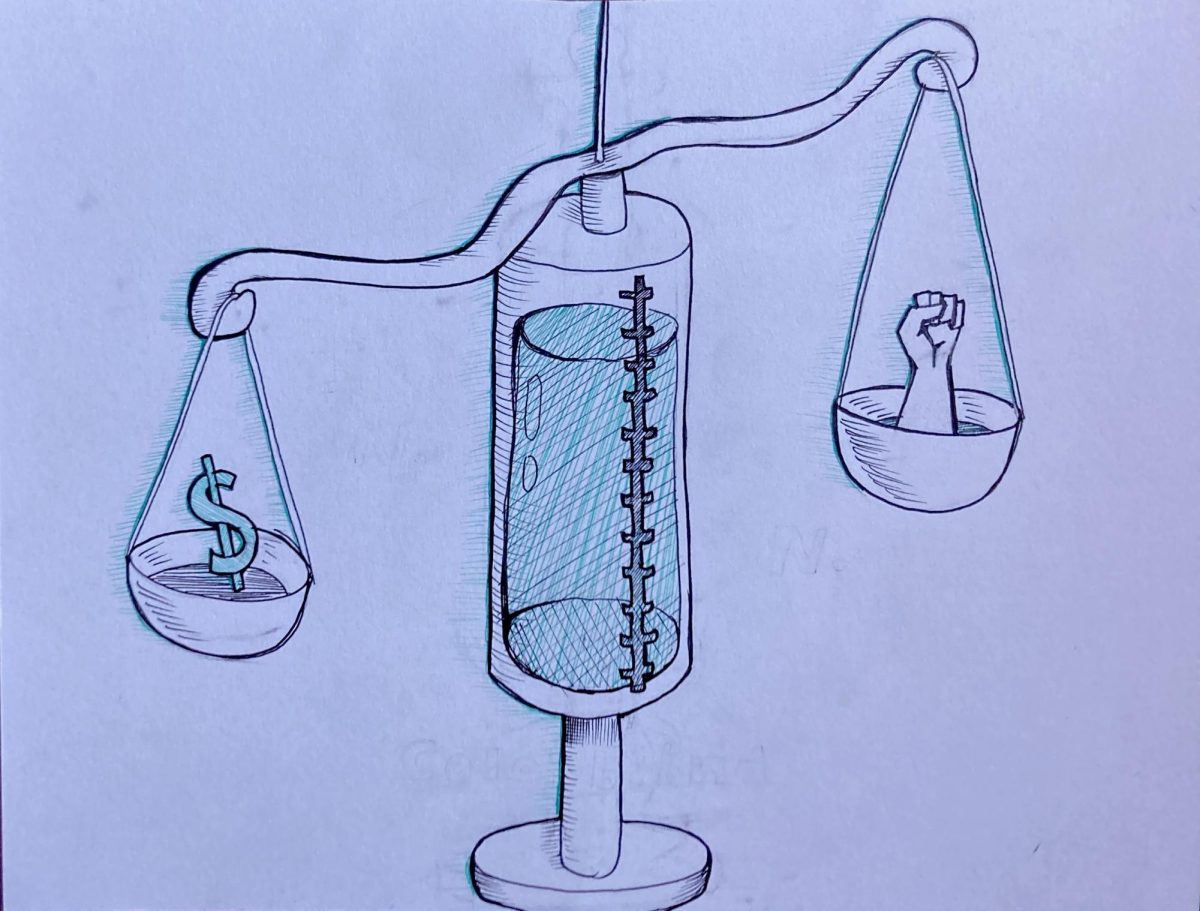

But the cure for TB was discovered in 1943, and additional improved drugs to combat TB have been created since. By contrast to the world’s death rate, the mortality rate for TB in the United States is approximately 0.2 per 100,000 people. As John Green highlights, “The cure is where the disease is not, and the disease is where the cure is not.”

It turns out that the cause of death for these some 1.3 million individuals is not entirely tuberculosis, but the presence of the profit motive, preventing the cure from reaching the many impoverished communities it ravages. The leading cause of death among TB patients is arguably human apathy.

This means that whether an individual with a treatable malady is condemned to death or not depends largely on what mound of earth they happened to be born upon and who happened to lay claim to that mound of earth centuries prior.

“Medical equity” is defined by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services as “the attainment of the highest level of health for all people … regardless of race, ethnicity, disability, sexual orientation, gender identity, socioeconomic status, geography, preferred language, or other factors.” Medical equity is the goal of humanitarian medical endeavors. However, the fact is that medical inequity, characterized by disparate access to health care, is a pestilent threat to the fair and non-discriminatory treatment of, well, pestilence.

However, while medical inequity is certainly a much larger issue in the developing world, to ignore the fact that even the “developed world” suffers from medical inequity rooted in the profit motive and internal “us-vs-them” divisions would be folly.

In the United States specifically, while socioeconomic status plays arguably the largest role in determining medical inequities, the social understanding of race is intrinsically linked with the issue of who has consistent access to quality healthcare and health insurance. The Commonwealth Fund, a private foundation dedicated to advancing health distribution and equity for all, reports, “Health outcomes, as measured primarily by mortality rates and the prevalence of health-related problems, differ significantly by race and ethnicity.”

According to statistics compiled on the Commonwealth Fund’s scorecard, “Achieving Racial and Ethnic Equity in U.S. Healthcare,” Black and Indigenous peoples are more likely to die from treatable conditions, more likely to die during labor and pregnancy, and are at higher risk for chronic illnesses. And Covid-19 had a disproportionately high human cost in Black, Latinx, and Indigenous communities, going even so far as to lower the life expectancies of these demographic groups.

There are many root causes of medical inequity, beyond even the classic corporate avarice. One of the most visible causes in the United States involves who is insured, and thus granted access to routine medical visits and pharmaceuticals, and who is not.

Signed into statute in 2010 by President Obama, the Affordable Care Act expanded federal health insurance programs and requirements in an attempt to insure those unable to afford a private insurance provider. Despite this, the national uninsured rate remains at approximately 10.4 percent – disproportionately so among Black, Latinx, and Indigenous peoples – with the New Mexico uninsured rate slightly higher still, at 11.5, according to the NM Department of Health. More statistics compiled by the Commonwealth Fund demonstrate that the uninsured rate for Indigenous New Mexicans is 31.1, for Latinx 15.9, for Black Americans 14, for White Americans 8.8, and for Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders 7.5.

This high uninsured rate for Indigenous New Mexicans is indicative of a larger trend present in the U.S. history of medical inequity, namely the systematic mistreatment of Indigenous health, which is largely perpetuated via generational trauma. NM Health’s Office of Health Equity states, “Obesity and diabetes among New Mexico youth are disproportionately higher in Native and Hispanic populations. Diseases of despair are highest among Native Americans, with NM ranking highest for alcohol related deaths in the nation.”

In addition to the presence of such health conditions rooted in poverty, sovereign tribes receive minimal funding from the federal government regarding health services, which goes to the Indian Health Service. And while Indigenous peoples are among the least insured demographic groups, they also experience homelessness at a rate higher than the general population. However, because application for federal healthcare services is done at the state level and requires proof of citizenship, those who are homeless have a more difficult path to obtaining health insurance, which only serves to widen the race-based divide within healthcare access.

Similarly, due to the citizenship requirements, those who immigrate to the United States “illegally” face the same barriers to gaining health insurance and required care. While many would argue that insuring these individuals is not a federal responsibility, it is undeniably an issue in medical inequity, which ties back to one’s access to care being predominantly the result of where one was born.

While medical insurance certainly is conducive to medical care and quality, it isn’t the end all, be all. Even with insurance, individuals nevertheless face unequal access to care for a variety of reasons. For starters, those insured under the ACA, who are often of lower income, cannot always afford to miss a day of work to go to a doctor, much less if they have children and must use their sick days to take care of their children when they are sick.

According to the New Mexico Legislative Finance Committee, 43 percent of New Mexicans are enrolled in Medicaid, with 77 percent of adult enrollees subsisting below the federal poverty level. If even a few of these individuals are living paycheck to paycheck, and struggling to feed their families, they may not be able to afford, say, the $15 co-pay for an emergency room visit.

What’s more, Medicaid does not provide coverage for every medical necessity. Spending and benefits of Medicaid vary per state, and while New Mexico spending is fairly middle of the road, the items that are not covered include dental work that is preventative, diagnostic, or orthodontic, which only further expands the socioeconomic disparity regarding access to medical care. (Additionally, medical supplies are not included in New Mexico’s Medicaid benefits, although pharmacy prescriptions are.)

Lack of access to primary care, for any reason, including a lack of insurance or not being a legal resident, means that conditions are more likely to fester and deepen into long lasting, perhaps life-threatening medical emergencies.

Although much of medical inequity is tied to socio-economic status and insurance, interpersonal racism does play a role. One of many examples is that breast cancer diagnoses are often delayed for Black women, resulting in higher fatalities. While this does in part result from the lower rates of insurance among minorities, as well as lower SES, statistics show that women and Black Americans tend to be taken less seriously by their doctors than white, cis-gendered men. (A majority of medical professionals, between 56 and 60 percent, depending on the source of data, identify as white.) Statistics show that minority health concerns are thus more likely to be ignored or diminished depending on the personal bigotry of some physicians.

Another factor that plays a large role in New Mexico’s medical inequity is the state’s large rural population. According to the University of New Mexico’s Rural Health Research Support Network, “In New Mexico, 30 of 33 counties are Health Professional Shortage Areas, and 60% of the population lives in rural communities.”

There is a large health disparity associated with living in rural areas by way of a simple lack of access to practicing physicians and up-to-date technology. The report explains that, in New Mexico, “Only 10% of physicians practice in rural areas.“ While living in rural areas does indeed tie into socioeconomic status, it is important to note that those impoverished in cities tend to have a different experience of medical inequity regarding those impoverished in rural areas.

An additional contributor to disparities in medical access and quality across the United States is the fact that although the nation has a mere 5 percent of the world’s total population, it accounts for nearly one-quarter of the world’s incarcerated population. The incarceration rate in New Mexico alone is particularly high, at 733 per 100,000 individuals, a number “higher than any democratic country on Earth,” according to the Prison Policy Initiative.

Medical access within prison systems is best described as lacking. Inmates’ health concerns are often disregarded. For example, according to the CDC, the rate of TB, as well as other infectious diseases, is higher among America’s incarcerated population. Interestingly, medical inequity between free and incarcerated people connects back to the high rates of alcoholism and diseases of despair associated with poverty, indicating that this is yet another means by which SES determines who has access to medical services.

Medical inequity is a vast issue whose advocates are growing more vocal, working to ensure that, as John Green would wish – whether it be a literal remedy or the systemic overhaul of health care access – the disease is no longer where the cure is not.