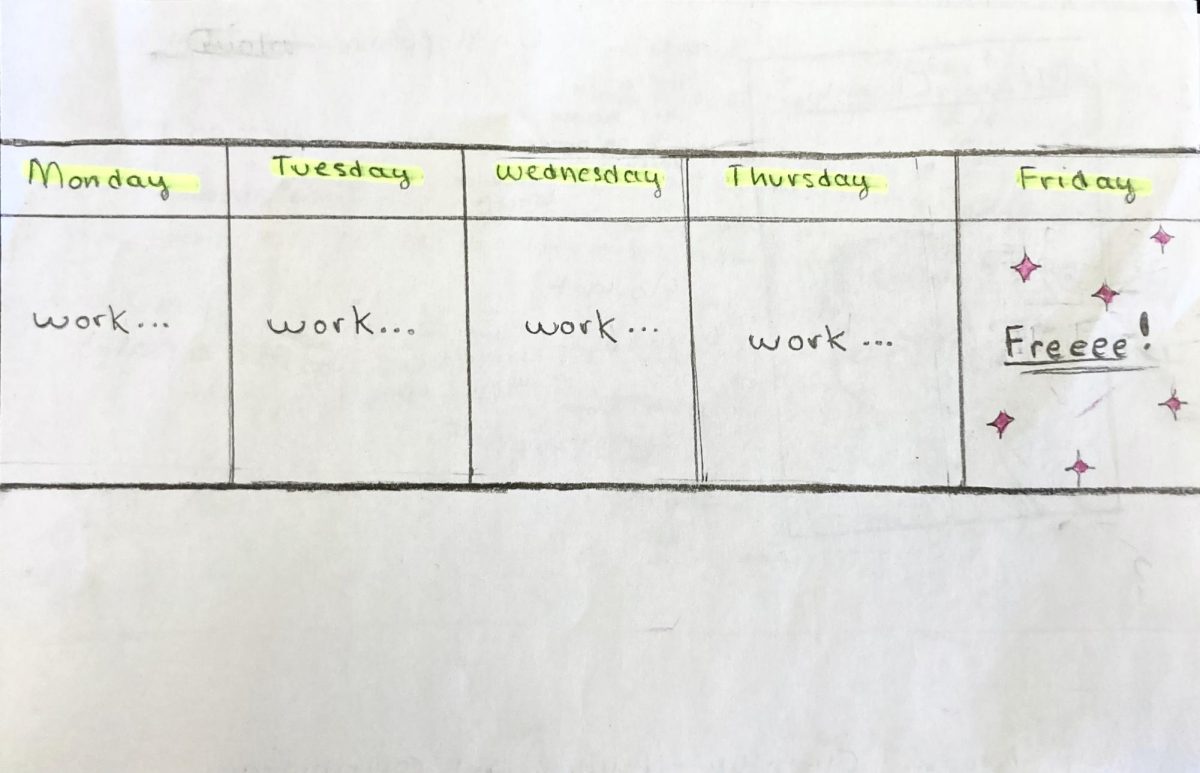

In 1930, as the Great Depression, like a sweeping pestilence, began to ravage the economic standings of many American families, famed economist John Maynard Keynes predicted, “In the 21st century a fifteen hour workweek will suffice.”

Previous economic trends had certainly illustrated that this would be the case. In 1916, the Adamson Act passed after a long and tumultuous campaign, implementing the eight-hour workday for overworked American railway laborers. In 1938, President Roosevelt signed the Fair Labor Standards Act, making eight hours the legal standard for the American workday. Additionally, in 1926, the early 20th century motor vehicle industry titan, Henry Ford, standardized his corporation with a five-day work week for his employees. And yet, the majority of modern day Americans toil away for the same 40 hours per week as was established over 80 years prior.

Keynes was evidently wrong, but he doesn’t have to be. There is a strong argument to implement the four-day workweek.

First, the four-day workweek has been shown to decrease employee stress levels and burnout, while improving both mental health and productivity. Conversely, opponents of the four-day workweek argue that these improvements are short lived and that the lessened labor hours actually contribute to higher burnout and stress levels due to having to complete the same amount of work in a shortened period of time.

However, many real world examples illustrate the opposite. For instance, one study in the United Kingdom implemented a shortened workweek while maintaining pay levels in multiple companies over an extended time period and found that employees reported feeling much better, not worse, as opponents of the four-day workweek predicted. Forty percent of these employees reported less work-related stress and improved mental health, while 71 percent reported less burnout, and 96 percent reported a preference for the four-day workweek.

What’s more, quite a few countries already have four-day workweeks, including Japan, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Canada. Many of these countries, namely New Zealand, Sweden, Denmark, Canada, the Netherlands, and Iceland, are among the world’s “happiest” nations, according to the World Happiness Report. While many factors contribute to a feeling of life satisfaction, more hours to be spent at one’s own discretion undoubtedly plays a role in creating a happy population.

Many of these countries not only rank high in happiness on the global stage, but in productivity as well. Japan, Sweden, Denmark, and the Netherlands have some of the highest productivity levels worldwide, according to data from the World Bank, all of which have implemented the four-day work week.

To quell any burgeoning ideas that this could result from an external factor and not the length of the work week, this same increase in productivity occurred when Henry Ford allowed his employees a full two days off in 1926. His employees were among the happiest “unskilled laborers” in the nation, and the productivity — and therefore the profitability — of Ford assembly lines skyrocketed. It was symbiosis in its finest 1920’s form. If an increase in happiness is not enough to persuade one on the validity of the shortened workweek, perhaps an increase in productivity is more convincing.

The four-day workweek operates on the concept of removing unnecessary distractions from work life, such as many meetings and menial tasks, which often serve more as a justification to management than an actual benefit to employees. Besides, if individuals are being paid for the amount of work and quality of work that they produce, and the four-day workweek is aimed at increasing the efficiency of the work day, then why would anyone have to work longer days? In the United States, where the four-day work week was established, American workers truly would be working an average of 32 hours each week.

Additionally, it is important to note that the conditions and societal structure that created the five-day workweek are simply outdated. First, the definition of what productivity even is has shifted significantly from the first wave of American labor standard reforms. According to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 32.4 percent of Americans were employed in manufacturing in 1910, whereas by 2015, this number dropped to 8.7 percent. Conversely, in 1910, 21 percent of Americans were employed in the service industries, while in 2015, 39.6 percent worked service industry jobs.

This trend isn’t dissipating any time soon, especially considering the introduction of robotic labor in manufacturing industries. This means that overall productivity no longer has to be measured by the amount of goods exiting a factory, something that can certainly be increased through more labor hours, and rather by the quality and attentiveness of service and sales, something that can only be increased through positive employee mental health.

Second, when the five-day work week was implemented (and for many decades following), the standard structure of American households had one individual who was capable of taking care of domestic tasks, such as ensuring that children were fed, bathed, and educated, while the spouse worked to provide for the household. This meant that the weekend was a time to savor life and family. Yet now, the typical American household has both parents working eight-hour shifts, five days a week, and often, due to the 1950’s demographic shift to suburbia, with very long commutes. This leaves little room for the necessities of domestic life, such as cooking and cleaning, meaning that only a comparative sliver of time can be spent engrossed in hobbies or socializing, or whatever else people find delight in doing. The four-day work week would provide at least an extra day for Americans to focus on something other than working, both at work and home.

But if human life being imbued with some amount of meaning isn’t persuasive enough, perhaps arguments of capitalistic gain will be.

Much as its predecessor did, the four-day workweek has the potential to bolster the American economy and thereby its position on the world stage as an economic superpower. With the two-day weekend in 1926, when workers had more free time, they spent more on entertainment and home goods. This fortified the American economy; these benefits increased as more and more employers implemented the five-day workweek. The same increase in spending will likely occur today if people could spend a third day outside of their jobs, which would benefit many industries, including entertainment, construction, restaurants, automobiles, and more.

Granted, the opulence and over-speculation of the 1920s did play a large role in causing the Great Depression. But with modern government checks and balances, the economic activity engendered by the four-day work week would likely have the opposite effect, especially considering that there would not be more capital in circulation; rather it would be spent in more sectors.

That being said, it is important to note that the ultimate goal of decreasing labor hours is about de-commodifying the American workforce, not further benefiting the privileged.

The four-day workweek would act just as symbiotically as the five-day workweek did. The American individual would live a better life, and as a result would labor with improved productivity, efficiency, and ultimately, greater profitability for the employer.

Many acknowledge that the real threat that employers face with the four-day workweek is not economic, but social. This is because the less that American citizens toil, the more they will likely understand there truly is more to life than working, and it will be harder for corporations to justify their own self-interest as for the benefit of all.

Here’s what a few Santa Fe High community members have to say about the four-day workweek:

Mr. Caldwell, the AP U.S. Government and AP European History teacher, states, “I think there’s a lot of evidence that suggests the four-day workweek leads to productivity in business, but I would like to see more on the four-day workweek for educators and schools… especially during… high school.”

“I personally had a four-day school week throughout elementary school,” states senior Merrick Word-Brown, “and I feel like I learned just as much as my peers from other schools that had five-day weeks.” He continues, “There’s a lot of busy work and wasted time at school, and with an emphasis on quality instruction, you could learn just as much in four days a week.”

A student who wishes to remain anonymous states, “On the one hand, I think there is definitely a lot of merit to the idea that if you have less time you are going to use it wiser, and being at school there are a lot of wasted hours that aren’t productive. On the other hand, what are those new hours going to, and are they going to be used well?”

Another student says, “We probably should be able to have a four-day work week.… Overworking is obviously not good for humans, but at a certain point, work does provide some benefits.”

“I think [the four-day work week] is actually really good,” says Gabbi Herbert. “Our mental health is clearly out of whack, and I feel like cutting down the amount of time that we are in school and work and in an environment when we aren’t expressing ourselves is something good to get away from.”