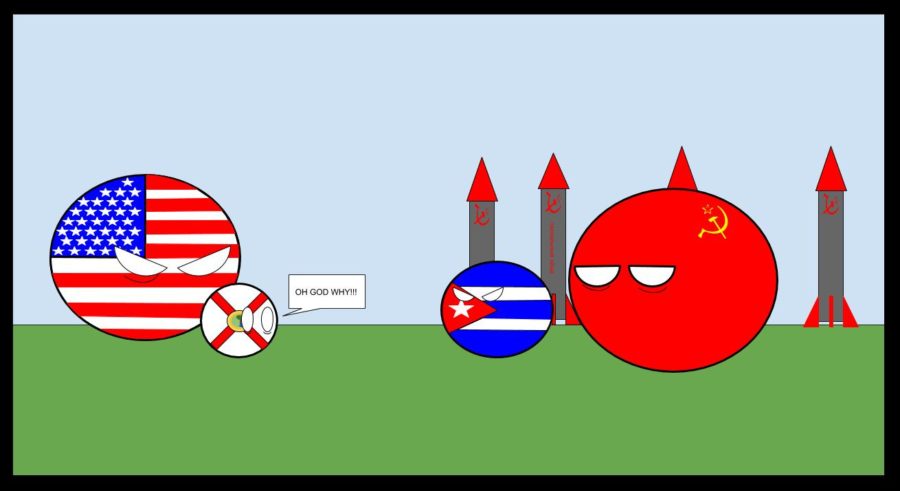

The Cuban Missile Crisis, Part 2

November 1, 2019

On Oct. 22, 1962, President Kennedy signed off on the quarantine authorization of Cuba. Once the first Soviet cargo ship was inbound in the exclusion zone and started to turn back, those Soviet missiles couldn’t be delivered to Cuba, and Krushchev finally agreed that war was not an option and must be avoided if at all possible. But withdrawing from this because of U.S. tension could destroy him politically, so he offered an idea: He would withdraw missiles from Cuba if the U.S. promised to never invade Cuba. As an add-on, he requested that the U.S. remove its missiles from Turkey.

When Kennedy received this offer he was in favor of it, but his advisors claimed that a Soviet invasion in Europe could happen soon. Plus, removing the missiles and promising no invasion of Cuba could possibly violate NATO agreements.

In the Carribean, a Soviet submarine hadn’t heard from Moscow. With the U.S. Navy using grenades and depth charges, they believed the war was on, and the leading officers voted to launch their nuclear torpedo on U.S. ships. Two officers voted yes, but another voted no; to launch this torpedo, all officers had to vote yes. When the sub surfaced, it was surrounded by U.S. ships maintaining positions.

Finally Kennedy reached a verdict. He would agree to never invade Cuba if the Soviets removed their missiles from the island. But he couldn’t publicly trade this for removing U.S. missiles from Turkey. Under the table, however, the agreement was made, and the U.S. removed its missiles.

Hours later, Krushchev received the letter and accepted Kennedy’s request. There was a public letter for accepting the promise of no Cuban invasion for the removal of Soviet missiles, and a secret one for U.S. missiles to be removed from Turkey. The next week, missiles were shipped out of Cuba and Turkey and war was averted.

Until 1965, when the Vietnam War began.