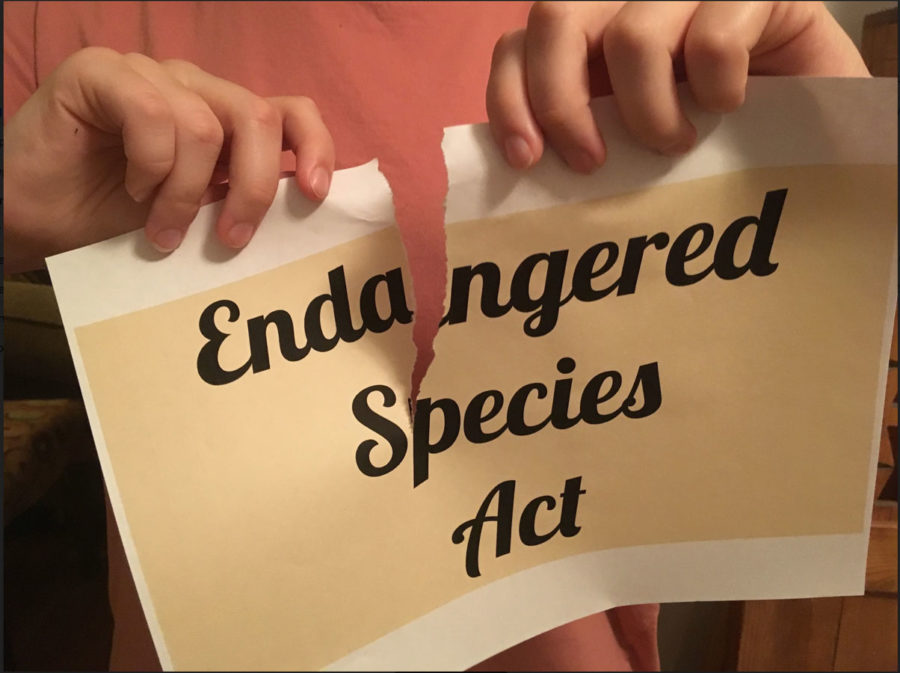

Endangered Species Endangered By ESA Revisions

October 3, 2019

The Trump Administration announced on Aug. 12 that it would be making revisions to the Endangered Species Act. These changes would make it easier to take species off the list even when they are still endangered. Regulators would also be able to assess how much money it would take to save a species, which could be a reason for their being removed from the list.

One endangered animal that is being impacted by these new rules is the Black Footed Ferret. Organizations are working to help preserve the endangered black-footed ferret population, but they face new complications from these revisions made to the ESA as well as an outbreak of rabies in prairie dogs in Colorado.

Black-footed ferrets, the only wild population of ferrets in North America, have been endangered for decades. In fact, they were thought to be extinct until 1981. They used to populate the western plains bountifully until pioneers began to hunt and poison prairie dogs, the black-footed ferret’s main food source.

There were estimated to be just 88 black-footed ferrets in the wild when their believed-to-be extinct population was found again, but due to plague and Canine Distemper (a virus that attacks the respiratory, gastrointestinal and nervous systems of puppies and dogs), the population had dropped to 18. The last wild population was brought into captivity in 1987 so they could be saved from extinction and their population could grow while being monitored and protected without facing the dangers of the wild, according to the Center for Biological Diversity.

Programs have been working to help reintroduce black-footed ferrets into the wild, and there are now an estimated 300 to 400 surviving. According to the Center for Biological Diversity, reintroduction sites have been located in several states such as Arizona, Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, South Dakota, and New Mexico.

There have been six reintroductions to Colorado, with the first in 2001. From 2005 to 2007, reintroductions took place at Vermejo Park Ranch in Northern New Mexico and, in 2009, the very first black-footed ferret was born in the wild since1987. Other reintroductions have occurred in New Mexico since, including a release in Wagon Mound in 2018, described in the New Mexico Land Conservancy Newsletter of Fall 2018.

In Colorado there has been a recent outbreak of bubonic plague in prairie dogs, centered around the Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge. Four Corners (where Arizona, Colorado, Utah, and New Mexico meet) is the most common location for plague outbreaks, including in humans. When the outbreak started in July 2019, the park was closed to try to contain the outbreak while the prairie dogs were treated with vaccines and their burrows were dusted with insecticide to keep fleas away.

The majority of Colorado’s black-footed ferret population lives in the refuge, where they are mainly located on the opposite side of the park from the infected prairie dogs. As of August 2019, there were no signs of infection in the ferrets, but the conservation programs protecting the ferrets are continuing to work to keep them safe from this outbreak, as diseases such as plague are one of the largest threats to the growing black-footed ferret population, according to the World Wildlife Fund.

Another threat the black-footed ferrets face is human ignorance. The ESA revisions will make it more challenging to protect endangered species from dangers they face, especially the impacts of climate change, according to Lisa Friedman, writing in The New York Times.

The black-footed ferret is among the top 10 most endangered mammals of North America, and they need the help of humans to preserve their habitats and food sources, as do many other endangered animals. But this will become even harder to accomplish with the revisions to the ESA.

Black-footed ferrets are indicators of a healthy ecosystem. They live in prairie environments, but these are being increasingly affected by agricultural and housing projects as well as climate change, limiting the amount of suitable habitat.

Grasslands and prairies are sensitive to climate change, as droughts are occurring more frequently and both the lowest and highest temperatures are becoming more extreme.

These changes can cause a loss of habitat and further endanger wildlife, and they will make it hard to protect the close to 1 million endangered species, many of which, without help, are anticipated to become extinct, some within decades.

It has taken a lot of time and effort to help the population of black-footed ferrets grow, and even now their population is limited and in constant threat of danger. Without the programs that originally took the remaining ferrets into captivity in 1987, they would almost certainly be extinct today, and the same goes for many endangered animals like the bald eagle and the grizzly bear who were brought back by conservation services and protected by conservation laws.

The recent plague outbreak has demonstrated the need for these protection programs, as the epidemic would have spread much wider without them and would have most likely reached the black-footed ferret population, resulting in large-scale deaths.

Max • Oct 14, 2019 at 2:53 pm

Save the Endangered Species Act! Save the black-footed ferret! Everyone turning 18 in the next 12 months should register to vote, and support candidates who believe in science and recognize the crisis that all living things are facing as a result of misguided leadership. Thank you Ciara for helping keep us informed!