Dawn Probes End, Curiosity 360-View, Ceres’ Bright Spot

September 17, 2018

By Maximilian Looft

The end of NASA’s Dawn probe

After an 11-year journey, NASA’s probe Dawn is finally reaching the end of its incredible mission.

Dawn, about the size of a tractor trailer (65 feet long), launched in 2007 from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station on a Delta II-Heavy Rocket with the destinations Vesta and Ceres. The goal was to survey these dwarf planets which together comprise 45 percent of the asteroid belt.

Dawn reached Vesta, a 326-mile diameter asteroid (the second largest object in the asteroid belt) on the July 16, 2011, where it orbited for a year, scanning and taking photos before de-orbiting in 2012, heading to Ceres.

Three years later, Dawn finally reached Ceres where it learned many spectacular details about the dwarf planet. Scientists were able to discover from the geography and chemistry of the surface that Ceres once had an ocean.

“What we found was completely mind-blowing,” says Carol Raymond, principal investigator of the Ceres mission. “Ceres’ history is just splayed all over its surface.”

But back to Vesta. Scientists noted that there were many more large asteroid impacts on its surface than expected, suggesting that the asteroid belt had had many more asteroids early on than scientists previously believed.

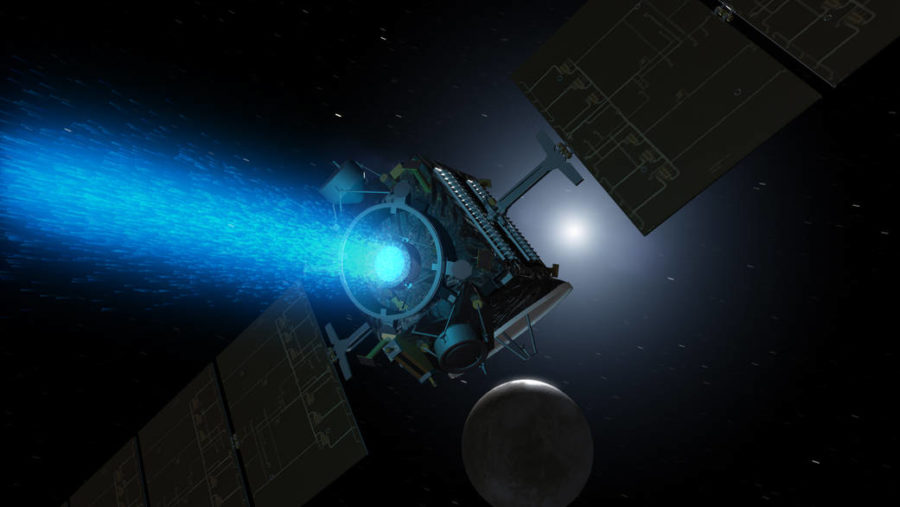

Not only did the Dawn mission reveal the history and secrets of these two bodies, but it allowed for many engineering feats as well, such as being the first manmade object to orbit an asteroid, then de-orbit, and orbit around another one. Dawn is also one of the few spacecraft to use an ion drive, an engine that creates thrust by accelerating positive ions with electricity.

Dawn accomplished many scientific and engineering feats over the past 11 years, even gaining an extra three years of operation instead of the originally planned eight years. But it’s finally running low on fuel. It is estimated that Dawn will lose fuel and connection with Earth sometime between September and October.

Many will be saddened over Dawn’s end but will also celebrate its many accomplishments.

Curiosity at Vera Rubin Ridge

On September 6, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory posted a 360-view video of the Mars Curiosity rover, taken on August 9 under the slowly clearing skies:

The video itself is stunning. Being able to look around the Vera Rubin Ridge in up to 8K resolution (if one’s computer or phone can handle it) from Curiosity’s point of view is spectacular. Looking toward the Northern Crater Rim, one can see what appears to be small mesas scattered about, as well as the dust storm of Mars that is still slowly clearing.

Looking back the opposite way reveals Mount Sharp, otherwise known as Aeolis Mons, which is the central peak within Gale Crater where Curiosity first landed six years ago, rising 3.4 miles.

Surrounding the rover is Lakebed Mudstone, hard remnants of what used to be a lake and where earlier this year Curiosity found remnants of organic material under the ancient sediment.

Right in front of Curiosity is the “Stoer” drill hole, where Curiosity gained a new rock sample after two unsuccessful drill attempts earlier in August due to surprisingly hard rocks. The drill hole gained the name Stoer from a town in Scotland where important discoveries of early life on Earth have been made.

Finally, looking down at Curiosity itself shows the many instruments that cover the rover, as well as signs of the obvious harsh Martian environment, such as dust that covers the rover and a puncture in one of the wheels. But even through the tough conditions, Curiosity pushes on.

Bright spot on Ceres

Even though Dawn will lose fuel and spend the remainder of its silent years orbiting Ceres, the dwarf planet still gives fascinating details of the bright spot of Ceres.

First discovered in 2015 by Dawn, the images of this bright spot were captured just 22 miles away in orbit, showing the 57-mile wide crater that gave the bright glow. Further examination shows that there are many of these bright spots, and they consist of sodium carbonate.

This evidence hints that there might have been surface lakes on Ceres, or even reservoirs right beneath the surface, and that water could have made its way to the surface from fissures from deep underground. Dawn’s first target, Vesta did not have any signs of these saltwater lakes, which made Ceres a much more interesting target to study.