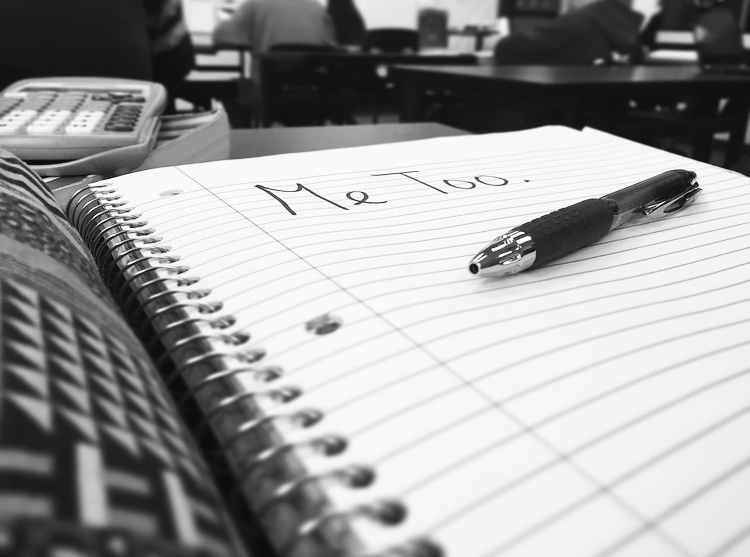

Schools Say, “Me Too”

February 1, 2018

“To the time when nobody ever has to say ‘Me too’ again,” said Oprah Winfrey at the end of her Cecil B. DeMille Award acceptance speech at the Golden Globes in January, addressing young girls around the globe. She spoke of a future free of gender inequality and abuse, stating that the time for that kind of behavior is up, and a new day is now “on the horizon.”

“Me too” — two words that, first shared on social media in 2006 by Tarana Burke, have spread virally over the past few months in the form of a hashtag and have been used to expose the all too enormous presence of sexual assault and harassment that has affected the lives of countless people in today’s world.

But what about the youth Winfrey was addressing?

“The idea is so foreign to people, that there could be sexual assault and an epidemic of sexual harassment and assault in schools,” said Esther Warkov, executive director of Stop Sexual Assault in Schools, a nonprofit organization she co-founded after her own daughter was raped during a school field trip in 2012.

SSAIS was created to address K-12 students’ rights regarding sexual harassment and assault in schools. “Most people think that schools are a safe place to send their kids,” Warkov said, “when that’s not really true.” She explained that SSAIS works to provide resources to students, K-12 schools, and organizations “so that the right to an equal education is not compromised by sexual harassment, sexual assault, and gender discrimination.”

At the beginning of January, the organization also launched the #MeTooK12 Campaign to spread awareness about how this issue affects youth. According to Warkov, the hashtag spotlights the widespread sexual harassment that students experience before entering college or the workforce, and underscores the urgency of addressing this problem in early education.

“Obviously we want to pay homage to the creators of #metoo, and at the same time we want to show that #metoo is a movement that spreads horizontally,” she said. “By linking the K12 part of it, it shows that there is really not a separation between K12 and #metoo; it’s one massive problem that actually starts in childhood.

“Students are probably the most vulnerable in this entire problem. Because they’re often unable to speak out for themselves, their complaints are silenced through intimidation and fear — fear of retaliation, fear of punishment, fear of social isolation for reporting — so it’s really important that we have a hashtag that talks about their unique vulnerability.”

This “vulnerability” is backed up by data.

Although it is rarely reported by both students and schools — despite the fact that, according to Warkov, schools are required to collect data on this issue — in 2014, the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights reported receiving more sex-discrimination complaints than ever. In 2011, the American Association of University Women found that nearly half of all students surveyed experienced some sort of sexual harassment over the course of the school year, and 87 percent said it had a negative effect on them.

“The prevalence of sexual harassment in grades 7–12 comes as a surprise to many, in part because it is rarely reported,” concluded the AAUW. “Among students who were sexually harassed, about 9 percent reported the incident to a teacher, guidance counselor, or other adult at school (12 percent of girls and 5 percent of boys). Just a quarter (27 percent) of students said they talked about it with parents or family members (including siblings), and only about one quarter (23 percent) spoke with friends.

“Girls were more likely than boys to talk with parents and other family members (32 percent versus 20 percent) and more likely than boys to talk with friends (29 percent versus 15 percent). Still, half of the students who were sexually harassed in the 2010–11 school year said they did nothing afterward in response to sexual harassment.”

As #metoo moves into schools, Warkov stresses the age of this issue and how addressing it is long overdue: “This has been on people’s radar for a long time, but no one [has really done or is] really doing anything about it for the most part,” she said.

She thinks that most kids aren’t educated enough about this subject, and that anything from classes on the subject to posters on the walls or daily announcements about the issue could make a difference. “I would like to see schools supporting anti-sexual harassment campaigns in school,” she said. “Every year of a student’s education, beginning in kindergarten, there should be age-appropriate education about sexual harassment [and] what constitutes sexual harassment.”

Sophie Colson, a senior at Santa Fe High, agrees. “I don’t believe that enough teens are educated on this,” she said. “It’s something that isn’t dealt with effectively enough in sex education, nor in any discourse. People don’t want to talk about it because it’s uncomfortable, but if we turned a blind eye from every uncomfortable thing, there would be no change.”

SSAIS has put all of its education online, allowing students around the country to access resources that can help with anything from how to get help if they’re being sexually harassed and their school is being unresponsive, to how to start a gender equity club. “Anyone that wants to learn about their civil rights can do so by accessing all the resources on our website,” Warkov said.

Sophie stresses the important role young people play in all of this: “I think that the youth should be getting more involved in the movement, and should be calling out their friends — male, female, non-binary — it doesn’t matter who you are, as long as you open your mouth and take action.”

This movement affects everyone. “It’s not just a female problem…students of all genders are sexually harassed, boys are sexually harassed…LGBTQ students are harassed at the highest rate,” said Warkov. “This isn’t just a movement to protect female students — it’s to protect all students.”

Warkov believes that everyone in the school community needs to get involved and emphasizes the importance of following Title IX, the federal civil rights law that prohibits sexual discrimination in federally funded educational settings (including both public and some private schools). This, Warkov said, is something many schools are lacking. “The responsibility is on the schools to do the right thing, and they’re just not doing it for the most part.”

Santa Fe Public Schools defines sexual harassment as “harassment based on sex or of a

sexual nature; gender harassment; and harassment based on pregnancy, childbirth, or

related medical conditions.” The Sexual Harassment Policy contract states, “Harassment occurs when unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature is so severe, persistent, or

pervasive that it affects a student’s ability to participate in or benefit from an education

program or activity, or an employee’s work environment, or creates an intimidating,

threatening or abusive educational or work environment. A hostile environment can be

created by a school employee, another student, a parent or even someone visiting the school,

such as a student, or employee from another school.”

If an SFPS student feels they are being harassed or discriminated against in the school system on the basis of sex (or anything else such as race, national origin, disability, age, etc.), the district offers several methods to report it (compliant with SFPS’s Board of Education Policy 330), including talking to a district or school employee and filling out a District Complaint Form, which is available on the SFPS website.

Warkov stresses that increasing the reporting of this kind of behavior in schools is just one of the changes that will result in changes in society. “Students have years to [build poor habits] of sexual harassment and even sexual assault in K-12 schools, so if you want to address the problem at the source, you have to stop enabling this kind of behavior,” she said. “The school is a microcosm of the larger world, so as the change is made at school, there’s going to be a beneficial effect on society because you won’t see all of these perpetrators feeling that they can continue this sexual harassment in college and the workplace.”

Isaac Hernandez, another senior at SFHS, agrees that a big part of this issue is entrenched attitudes and that it must be taken seriously. “I think it’s the culture behind it,” he said. “A lot of people appropriate rape culture a lot of the time, and they make it seem like it’s okay. It’s like a watering down of it…so that adds to it.

“I think what schools could do is [provide] the resources, or have teachers call out students, or enforce [policies against the use of] those kinds of jokes or…sexual innuendos. Let them know that’s not okay, and that by saying those things they’re contributing to that kind of [culture].”

Now that this issue is being talked about more than ever with recent movements coming after #metoo, such as Time’s Up — a call for change from women in the entertainment industry to address inequality in the workplace that also took center stage at the Golden Globes—one can’t help but wonder what it means for teens today as they enter a bigger world.

“I hope that our society and our workplace are revolutionized,” said Sophie. “I think this movement needs to explode even more. This is really only the beginning of something that we are going to see grow in our lifetime. I would like to believe the punishment for this behavior becomes even harsher, and that there is a deeper understanding about the issue at hand, so much so that everyone everywhere is fighting to stop it.

“The #metoo/Time’s Up movement is very empowering to me,” she continued. “It means a lot to be a part of this revolution for women. I think this is the first time we are getting to see women taken seriously about their assault, and the removal of the shame around it for victims.”

And the future?

Warkov hopes that “schools are proactive in being trained in their responsibilities and abiding by the civil rights laws they’re supposed to.” She advocates for every school to have a trained Title IX coordinator whose job it would be to make sure that Title IX is properly implemented, including proactively addressing sexual harassment and assault before they occur, protecting students who report sexual harassment and sexual assault, and making sure that victims’ needs are prioritized over perpetrators’.

Sophie hopes to find the source of the problem. “The difficult thing is, yes, we can call out those who have assaulted, we can fire and ostracize them, which we should, but I think we need to start addressing and exploring the depth and root of the issue,” she said. “There is so much beyond calling out the assault; we must now start to address why.”

Isaac added, “I hope that we can just respect each other, have a loving community where a person shouldn’t feel like they’re endangered anymore, where we don’t have to have these kinds of talks about sexual harassment because it’s not there — maybe live in a world where we all respect each other, and women have the same opportunities and rights as men.

“The start of ‘a new day’ can only happen once discourse starts,” added Sophie, “and now that it has, now that all of this is being taken seriously, I think that anything is possible.”

EMPOWERU • Feb 2, 2018 at 1:44 pm

Great article! #MeTooK12 is shining a much-needed light on the sexual harassment and assault problem in K-12 schools. But they aren’t stopping there. Stop Sexual Assault in Schools also provides a FREE two-part video “Sexual Harassment: Not in Our School” that presents the facts on K-12 sexual harassment and assault as well as students’ Title IX rights and how schools should react to reports. Tell your story or show your support with #MeTooK12.