Why Free Speech Isn’t Always Free

October 23, 2017

Players kneeling, flags waving, people shouting: This makes people wonder, what expression is protected?

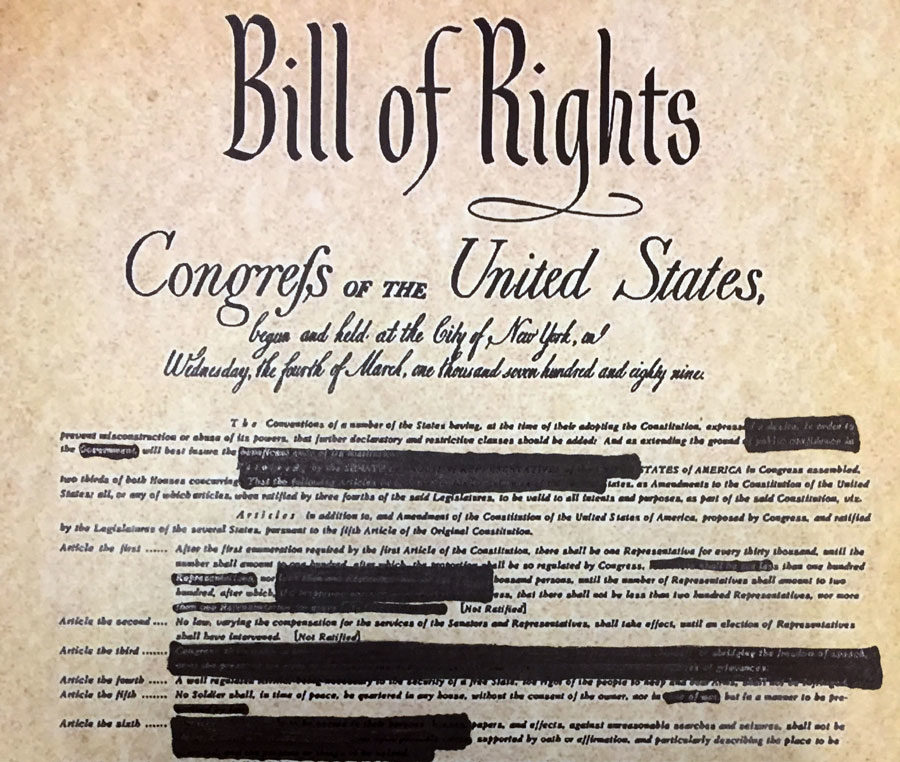

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution reads, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

There are exceptions to the rights guaranteed by the First Amendment, however: Free speech isn’t always free, and it isn’t always protected.

From NFL protests to free speech rallies, what we are allowed to say and how we are allowed to say it has become a heated debate in recent weeks. As the debate grows, it is important to question the two parts of a statement that together determine whether or not speech is considered to be protected, these two parts being the manner — how we say it —and the content — what we say.

Two categories of laws limit the First Amendment: content-neutral and content-based. In an article by Geoffrey R. Stone of the University of Chicago, Stone wrote, “Content-neutral restrictions limit expression without regard to the content or communicative impact of the message conveyed,” and “Content-based restrictions limit communication because of the message it conveys.”

Content laws are relatively few and far between in the United States, which has allowed for the so-called “free speech” rallies of late. Since the 1980s, numerous laws have been proposed to limit “hate speech,” commonly defined as derogatory or hateful expressions and statements. However, the proposed laws have often been invalidated by the U.S. Supreme Court on the grounds that hate speech is not an offensive expression, in the way that pornography is not, nor is it a true threat, such as a direct death threat or “fighting words,” which are defined as “words which would likely make the person whom they are addressed commit an act of violence,” according to the Legal Information Institute at Cornell Law School.

In the 2015 case Matal v. Tam, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled, “There is no hate speech exception in the First Amendment.” Justice Samuel Alito said, “Speech that demeans on the basis of race, ethnicity, gender, religion, age, disability, or any other similar ground is hateful; but the proudest boast of our free speech jurisprudence is that we protect the freedom to express ‘the thought that we hate.’ ”

This has created a nationwide divide on the topic of free speech, one that is based on the question of whether or not it is better to have complete freedom to express hate, or whether it is better to give up that freedom in order to create a safe society. Constitutionally, the first argument seems to prevail, as seen in the aforementioned case. However, that has not stopped protests against hate speech.

Examples of these protests include the events in Charlottesville and in Boston. In Charlottesville on August 11 and 12, a rally was held in support of “free speech,” as well as in opposition to the removal of Confederate statues. In Boston, protesters gathered a week later in support of “free speech” and as a follow-up to the Charlottesville rally.

However, in both of those “free speech” rallies, at least an equal number of counter protesters came out in opposition of the “free speech” being expressed. On August 19, the day of the Boston rally, Boston’s Mayor Marty Walsh tweeted, “Today Boston showed there’s no place for hate in our City. TY to all who peacefully stood up for our values, and the @bostonpolice.” Counter protesters in opposition to hate speech dwarfed that rally.

Another example of both sides of the free speech argument was the speech delivered at Georgetown University by U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions. A throng of counter protestors met him, each taking a knee and/or waving signs in protest of his arrival.

Sessions spoke of the necessity of upholding free speech at college campuses, alluding to prior events at UC Berkeley, where violent protests erupted after Milo Yiannopoulus, a prominent right-wing speaker, was invited to attend Free Speech Week at the Berkeley campus. At the event Sessions said, “A national recommitment to free speech on campuses and to ensuring First Amendment rights is long overdue,” as well as, “Protesters are now routinely shutting down speeches and debates across the country in an effort to silence voices that insufficiently conform with their views.”

This drew ire from protesters, some of whom displayed signs reading “Deport Hate,” “Free Speech Is Not Hate Speech,” and “Sessions is afraid of questions.”

However, there is also the issue of the manner of speech. Constitutionally, it is easier to limit the manner of speech than it is to limit its content, and as such multiple laws constricting the manner of expression (specifically, time and place) have become legally accepted. According to attorney Tasha Blakney, “All TPM [time, place, manner] restrictions must provide speakers with alternative channels for communicating ideas or disseminating information.” Blakney also wrote, “To pass muster under the First Amendment, TPM restrictions must be contentneutral, be narrowly drawn, serve a significant government interest, and leave open alternative channels of communication.”

Based on these exceptions, the government can implement laws limiting the time and place of speech as long as it still allows for another opportunity or means of expression for that speech. One popular example of this is screaming “Fire!” in a movie theater. While there is no law against screaming, or against the word “fire,” a person can be charged for screaming “Fire!” in a theater as it serves a government interest, that interest being safety of the civilians.

This brings forth the next argument, one that has been going on for over a year now: taking a knee during the national anthem. The custom of players standing for the anthem has only been in practice since 2009; prior to this, teams used to remain in the locker during the anthem.

While the legality of taking a knee during the national anthem has yet to be questioned, and no has law been put in place against it, there has nonetheless been opposition to it. Due to the lack of laws against protesting in this manner, there is no legal precedent that would make these protests illegal. However, we have a president who now advocates against it, and thereby advocates against free, legal expression.

When the issue came up at a rally in Alabama, President Trump said, “Wouldn’t you love to see one of these NFL owners, when somebody disrespects our flag, to say, ‘Get that son of a bitch off the field right now, he’s fired. He’s fired!’ ”

These statements drew protests as well as displays of solidarity with protesters from players and team owners, some of the team owners going as far as to stand with players. However, President Trump’s sentiments were also applauded by his supporters, displaying the divide on the subject.

This brings up the issue of the legally acceptable consequences for free expression. The First Amendment only actually protects public and government expression. This means that private enterprises, such as businesses, can fire an employee on the grounds of that employee’s expression. So it is completely legal for a sports team to fire a player for protesting during the national anthem.

One example of this was when Google fired an employee, James Damore, on August 7, for publishing a manifesto of discrimination and politically conservative ideologies. While Google described Damore’s behavior as leading to a counter-productive workplace and discriminatory practices, Damore argued that he was fired because his views differed from Google’s. Damore said, “There is a dominant ideology at Google, and anyone who dissents against that is either shamed or ostracized. And when it became apparent that I wasn’t backing down to shame, they had to fire me.”

This is the fundamental issue with free speech in the 21st century: When content is regulated to promote safety and to snuff out hate, it inadvertently limits criticism and discussion. When speech becomes limited in manner, expression as a whole becomes partly suppressed.

Legally, we are free to hate, and we are free to protest. This is, in and of itself, both a cost and a freedom: the ability to protest against hate, and the freedom to hate the protest.