New Mexico held its 2023 regular local elections on Nov. 7, which determined several city council members alongside several bill proposals. Perhaps the most controversial among these was the Santa Fe Affordable Housing Act, which would place a 3 percent excise tax on property transfers over $1,000,000, which would then bolster the city’s affordable housing trust fund.

Despite the undeniable increase this would have in the effective cost of property, the proposal passed with a staggering 73 percent majority. However, the tax, while significant, is still much less than many people would have hoped. The tax is only on amounts exceeding $1 million. For example, a $1.3 million home would have a $9,000 excise tax placed into the affordable housing fund.

But how much is 1.3 million really? According to Realtor.com, of the 572 single family homes currently for sale in Santa Fe, 242 of them cost more than $1 million, and 482 are over $500,000. The writing is on the wall: housing in Santa Fe is too expensive.

This excise tax will make a large difference in the amount of funding for the affordable housing initiative, but only because housing is already far past what most people can afford. According to United for Affordable Housing, a campaign to win permanent funding for affordable housing in Santa Fe, there is no neighborhood in the entire city where an average full-time worker could rent a two-bedroom apartment.

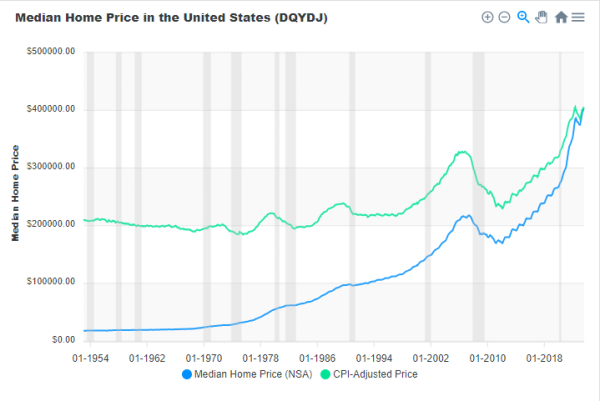

Santa Fe isn’t the only city affected by skyrocketing home prices. The graph below demonstrates median home prices since 1954, according to dqydj.com, a finance and investing website. Keeping in mind that the gray bars indicate recession and the gray line is adjusted for inflation, the price of housing was steady at around $200,000 until it began to rise at the end of the 1990s, with the beginning of the bubble that would lead to the recession in 2008. But after prices returned to stability, they shot right back up again and there’s no sign of them slowing down.

Even if a buyer could manage to afford the high prices, that might be the least of their concerns.

Gentrification is the process through which poorer, urban areas with dense cultural history and community are changed by wealthier people moving in for the novelty of the area. Often this influx displaces current residents, who then become removed from their community and culture.

Santa Fe has a long history of gentrification, with its roots beginning at the advent of the continental railroad. Pottery and tapestries were of great importance to the native population, but when wealthy people began touring the United States they purchased them, turning a personal, meditative practice into a business that was disconnected from what made it so special in the first place. Modern Santa Fe is viewed as an artistic cultural hub. As an example, Georgia O’Keeffe has an entire museum dedicated to her, which reinforces the prestigious reputation of the city’s art scene.

According to Pro-Move Logistics, a moving and storage company that provides information about the city, the cost of living is 14 percent higher in Santa Fe than the national average, largely as a result of its already wealthy population, which is capable of attracting businesses for the affluent, making a feedback loop. While the cost of living has been going up everywhere, current trajectories indicate that prices in New Mexico will continue to increase.

At the Dakota Canyon Apartment complex, on the Zia Path just down the road from Santa Fe High, a studio apartment costs $1,495 a month. Downtown, one-bedroom apartments start at $1,945, with many of their main advertising points being “live close to culture.”

Can young people in Santa Fe even hope to own their own home someday?

“I don’t know if it’s realistic,” says SFHS senior Quinn Keenan. “Many people within the newer generations are finding themselves stranded in some of the highest housing markets ever seen.”

Another student, Sofia Hickel says, “I think it’s way too high for no reason and it gets unrealistic for families that live here.”