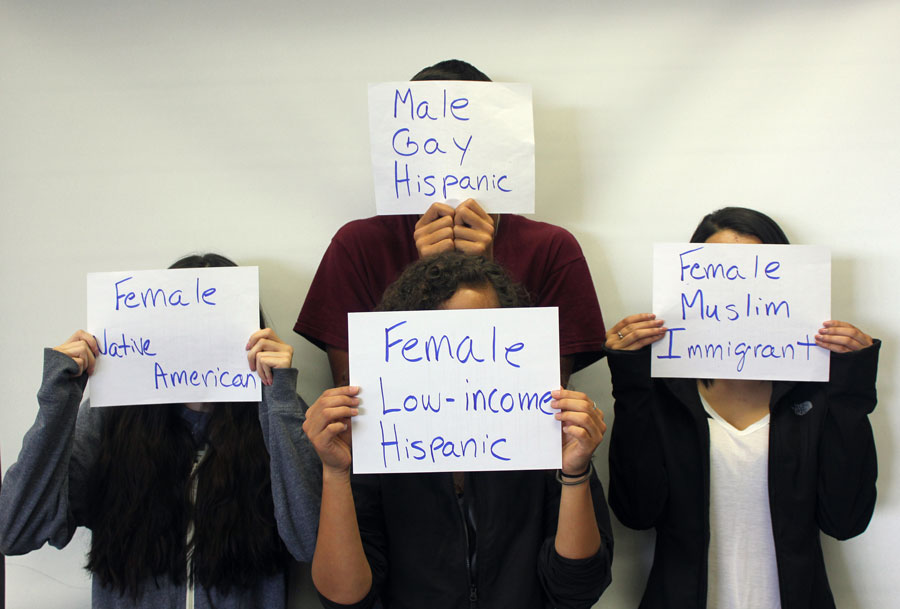

When Oppression Overlaps, Addressing Intersectionality Promises Progress

April 28, 2017

As politics become more complex by the day and a sore subject for most, many are turning to activism to make their voices heard. But what happens when the hot-button issues of today — racism, sexism, homophobia, classism, etc. — begin to cause conflicts within activist groups? And what can be done to prevent it?

When issues such as race and sexism become connected, they can have different impacts on different people. For example, sexism may be experienced differently for a woman of color than for a white woman. And homophobia may be experienced differently for, say, a 60-year-old Iraqi man and an 18-year-old New Yorker.

“Being gay, Hispanic, and a woman, I often feel as if I have three strikes against me for things that are out of my control,” said Santa Fe High senior Larissa Romero. “One thing I am happy about is that these ‘strikes’ against me have also empowered me and motivated me to create and help push along change that I wish to see.”

This is when intersectionality occurs.

Intersectionality is a term coined by critical-race-theory scholar Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw to describe the way “oppressive institutions” such as racism and sexism can become connected. The problem occurs when different types of oppression are isolated from each other and examined separately.

“Finally,” said “Washington Post” journalist Latoya Peterson upon discovering the concept of intersectionality, “I could stop fumbling for explanations about why I couldn’t separate my blackness from my femaleness, why different kinds of discrimination happened to me.”

In Crenshaw’s publication “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex,” she elaborates on her theory that treating sexism and racism as “mutually exclusive categories” — and antidiscrimination laws and activist groups that also treat the two as separate, non-interlapping concepts — often have their own internal conflicts.

While racism and sexism are not the only examples of intersectionality, they are easily seen due to their prevalence today and historically. According to the University of Virginia and History.com, the suffragette movement grew out of the abolitionist movement. Anti-slavery groups began to form during the 1800s, and as the conversation on slavery began to expand, so did the topic of voting rights, which developed into women’s rights. Women such as Lucretia Mott and Susan B. Anthony, who are often considered to be the original feminists, used the momentum of the abolitionist movement to build the women’s suffrage movement.

However, intersectionality quickly became an issue. While the women’s movement was essentially built on the anti-slavery movement, women’s suffrage saw little success when it began to separate the issues of racism and sexism. Instead of including women slaves in their suffrage movement, they began to exclude the issue of race entirely from women’s rights. And because slavery was at the time seen as the most important issue, what with the Civil War and all, women’s rights were pushed aside while legislation on slavery was passed.

But instead of incorporating the two together, government and activist groups further separated the two, causing progress in society and government to only occur for single issues at a time, which often marginalized minorities.

Traditional feminist and suffrage movements discouraged women of color, gay women, and women of different religions from bringing their individual issues into the women’s rights movement, believing that if race or homophobia got involved, attention would be taken away from women’s rights. Similarly, during the Civil Rights Era and Chicano movement, women were often discouraged from bringing to light the sexism they faced that was often interlaced with (and worsened by) their racial identity so as to keep the focus of the movement on racial equality.

Crenshaw describes the “marginalizing” that can occur among members of activist groups when one experiences racial discrimination, class discrimination, or even homophobia on top of gender discrimination, as opposed to another member who experiences only one. Such marginalization often causes only certain people in these groups to enjoy the benefits of progress being made.

Crenshaw used gender discrimination in the workplace as an example, stating that while laws had been passed requiring companies to be more gender-diverse in their hiring, black women saw little to no improvement in their job opportunities because when forced to hire women, companies usually chose white women. Such discrimination is common, according to the website Workplace Fairness.

Pay equality has always been an issue, but it is often ignored that while many women are paid less than men, black, Asian, Hispanic, and Native women are paid even less than white women. According to the PEW Research Center, the 115th Congress is the most diverse in history, yet it is still comprised of less than 20 percent women and less than 20 percent non-white men and women.

The “Washington Post” also did research on intersectionality and found that while it does cause the marginalizing of minority groups within movements, it can also cause “privilege checking” and sometimes even turns oppression into a competition. For example, Teaching Tolerance, a project of the Southern Poverty Law Center, explains that privilege, specifically “white privilege,” is “transparent preference for whiteness that saturates our society” and has become institutionalized to the point of prevalence, often without white citizens personally creating or promoting it. As a result of this societal privilege, those without it have begun to “check” those with it who don’t often acknowledge their privilege. Naturally this would cause tension. But this competitive oppression works in other ways too.

According to “The Guardian,” a surfacing argument against feminism is that because other women are technically more oppressed, women who don’t experience the same levels of oppression should not be campaigning for the progression of their own rights. “Try spending a day in Saudi Arabia where women are really oppressed!” cry critics of feminism in more developed countries. Major equality movements such as the women’s movement have consistently denounced such critiques as well as major news outlets such as “The Guardian,” “The New York Times” and “The Huffington Post.” The most common rebuttal to such an argument is that yes, others “have it worse,” but that doesn’t lessen or trivialize the discrimination of oneself.

While these negative outcomes can occur, the issue of intersectionality cannot wait because activist groups need to create “a vision of social justice that recognizes the ways racism, sexism and other inequalities work together to undermine us all,” writes Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw. “We simply do not have the luxury of building social movements that are not intersectional, nor can we believe we are doing intersectional work just by saying words.”

Because intersectionality is so prevalent, activist groups are beginning to see the importance in recognizing it in their movements. Environmentalist groups cannot ignore the lack of access that low-income citizens have to sustainable energy. Feminist groups cannot ignore the additional discrimination that non-white, non-straight women experience. And race-equality movements cannot ignore the increased violence and oppression that women of color experience compared to men of color.

While ignoring intersectionality is still an issue in activism, success can be found in recent events such as the Women’s March on Washington, which focused on a multitude of issues and included all genders, races, ages, and religions without excluding any issue in the protest.

Activists are now understanding that they can no longer focus on single issues and compartmentalize oppression. The struggle for progress has now expanded to involve inclusion, especially in such a complex, diverse and overlapping world.